Read the first installment in this series here: Jung’s Notions of Extraversion and Introversion.

In a previous post, I laid out Jung’s concepts of extraversion and introversion. In this post I will: (1) define Jung’s four function types of sensation, intuition, thinking, and feeling; (2) elaborate how the functions interact with extraversion and introversion to move us from two basic types to eight; and (3) describe how the functions are organized within a person to bring us from eight types to sixteen.

To briefly recap, Jung spelled out a theory of two attitude types in a 1913 essay in which he used the words extraverted and introverted to describe general tendencies of how a person could be in the world. An extravert, on balance, tends to orient, attend, and psychologically move toward objects out in the world, whereas an introvert tends to move toward the archetypes (primordial images) that those objects constellate. For Jung, this was not a matter of behavior, but rather of the flow and direction of libido, or psychic energy.

Not long thereafter, Jung expanded on this theory in his book Psychological Types (1921; all page numbers hereafter are to this work unless context dictates otherwise). Noting that “the conscious psyche is an apparatus for adapation and orientation [to the world]” (p. 518), he delineated four necessary and sufficient functions for orienting to anything whatsoever. To understand any phenomenon, we need to know that it is, what it is, what it is worth to us, and its horizons or possibilities: these correspond to the functions of sensation, thinking, feeling, and intuition, the four functions which he further subdivided into two basic categories: irrational and rational.

The Irrational Functions

The irrational functions of sensation and intuition, more often called perceiving functions nowadays, operate to a large degree passively. The irrational functions correspond to what Immanuel Kant in The Critique of Pure Reason (1781) called the cognitive power of sensibility, a receptive power capable of taking in impressions from the world. Through perception, we become aware of how the world is: only then can we rationally judge it, examine what it means and what it is worth to us, and so forth.

Jung’s distinction between sensation and intuition was somewhat ambivalent. At times he contrasted them by virtue of whether the mode of reception was conscious or not, defining “sensation as perception via conscious sensory functions, and intuition as perception via the unconscious” (p. 538). This definition can appear somewhat contradictory given that Jung also speaks of functions being or becoming more or less conscious: how can conscious perception be more or less conscious? Here it helps to think more in terms of time and space. Sensation is how we orient to concrete, here-and-now perceptual qualities of the world through our five senses, whereas intuition is a somewhat more ephemeral mode of perception that concerns how we take in the temporal and archetypal qualities of things in the world. In our time, when the concrete and rational are so over-valued, intuition can be a little hard to define and parse. Jung speaks of “the possibilities hidden in a situation” (p. 518) to characterize what we take in via intuition. Another way to think of it is that whereas sensation shows us what a thing is like now, intuition discloses what a thing could become. Sensation concerns the present and actuality. Intuition concerns the future and possibility.

The Rational Functions

The rational functions of thinking and feeling, more often called judging functions nowadays, operate more actively. The rational functions correspond to what Immanuel Kant (1781) called the cognitive power of understanding, a spontaneous power through which we actively cognize, categorize, and judge what we take in through the senses. Through judgments, we conceptualize what something is and what it is worth to us.

The purpose of the thinking function is fairly clear. Through thought, we cognize, judge, infer, deduce, and plan. Thinking is the function most people have in mind when they casually use the words ‘rational’ or ‘rationality.’ Jung was sensitive to the confusions that might arise in calling feeling a rational function. By feeling Jung did not mean tactile sensations (e.g., feeling that something is soft), hunches (e.g., the gut feeling that someone is lying to us), or the mere fact of having an affect (e.g., having an experience of sadness or anger). Rather, Jung used the word in a specific sense to refer to the subjective valuations we make of things. Feeling is expressed in whether we like, dislike, or are indifferent to something. Jung put the distinction thusly: “In the same way that thinking organizes the contents of consciousness under concepts, feeling arranges them according to their value” (p. 435). For Jung, feeling involves judgments just as much as thinking does, and thus “feeling values and feeling judgments—indeed, feelings in general—are not only rational but can also be as logical, consistent and discriminating as thinking” (p. 539).

From Two Types to Eight

In Jung’s model of the psyche, unconsciousness was the baseline state, and consciousness was an achievement. This is understandable, as most of our functioning goes on outside of our awareness, absent our conscious direction. As Nietzsche (1886/1966) put it as regards the thinking function: “I shall never tire of emphasizing a small, terse fact, namely, that a thought comes when ‘it’ wishes, and not when ‘I’ wish” (p. 24).

In each of us, all four functions always operate in our psyche, and most of this operation is more or less unconscious. In the course of development, each person over time tends to have one function dominate, and our individual typology (personality) hinges upon which function for which we are “best equipped by nature” (p. 450). This function, our superior function, is under greater conscious control, stronger and more supple, and more readily at our disposal. As Jung evocatively puts it, “Just as only one of the four sons of Horus had a human head, so as a rule only one of the four basic functions is fully conscious and differentiated enough to be freely manipulable by the will, the others remaining partially or wholly unconscious” (p. 520).

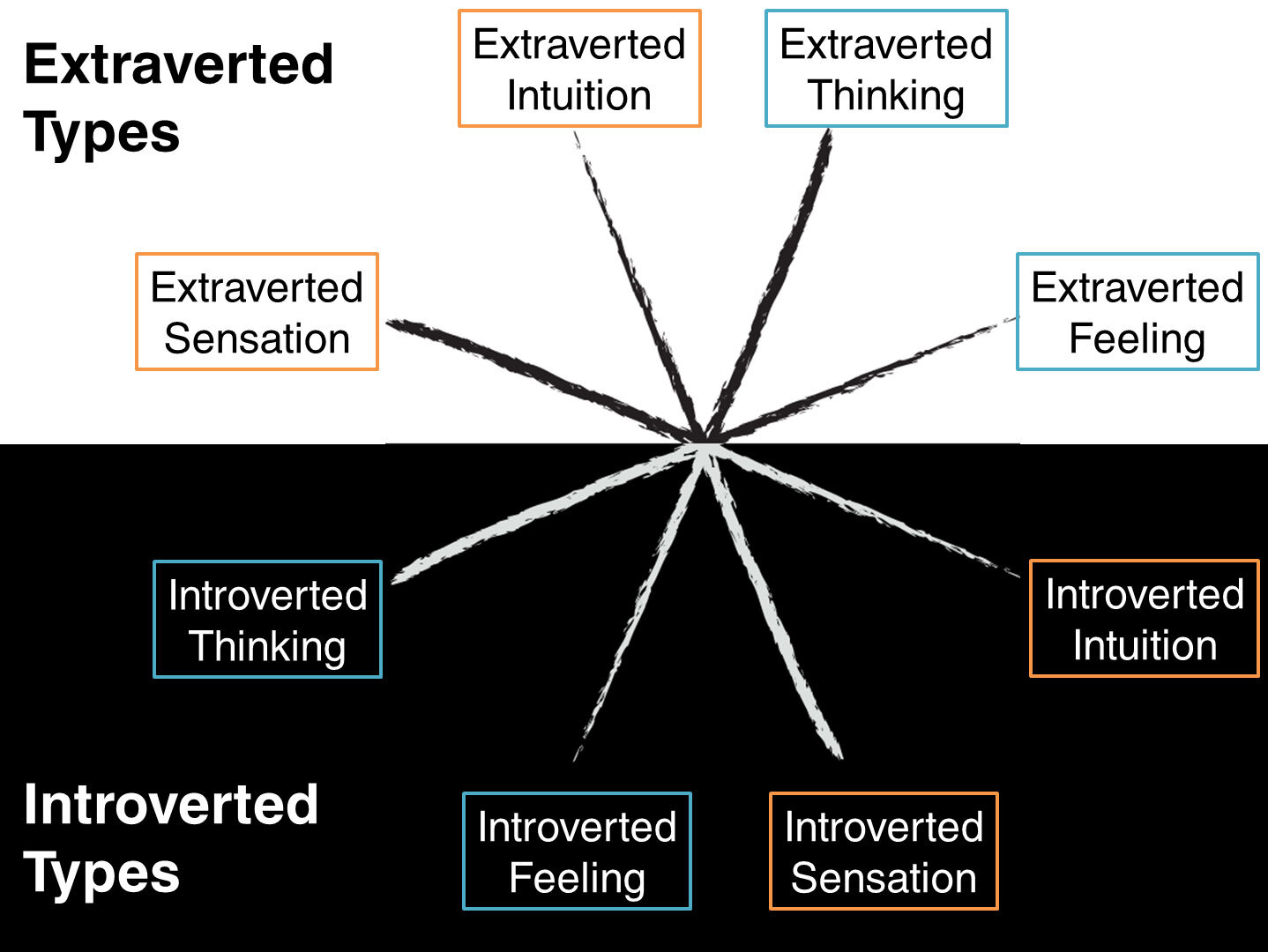

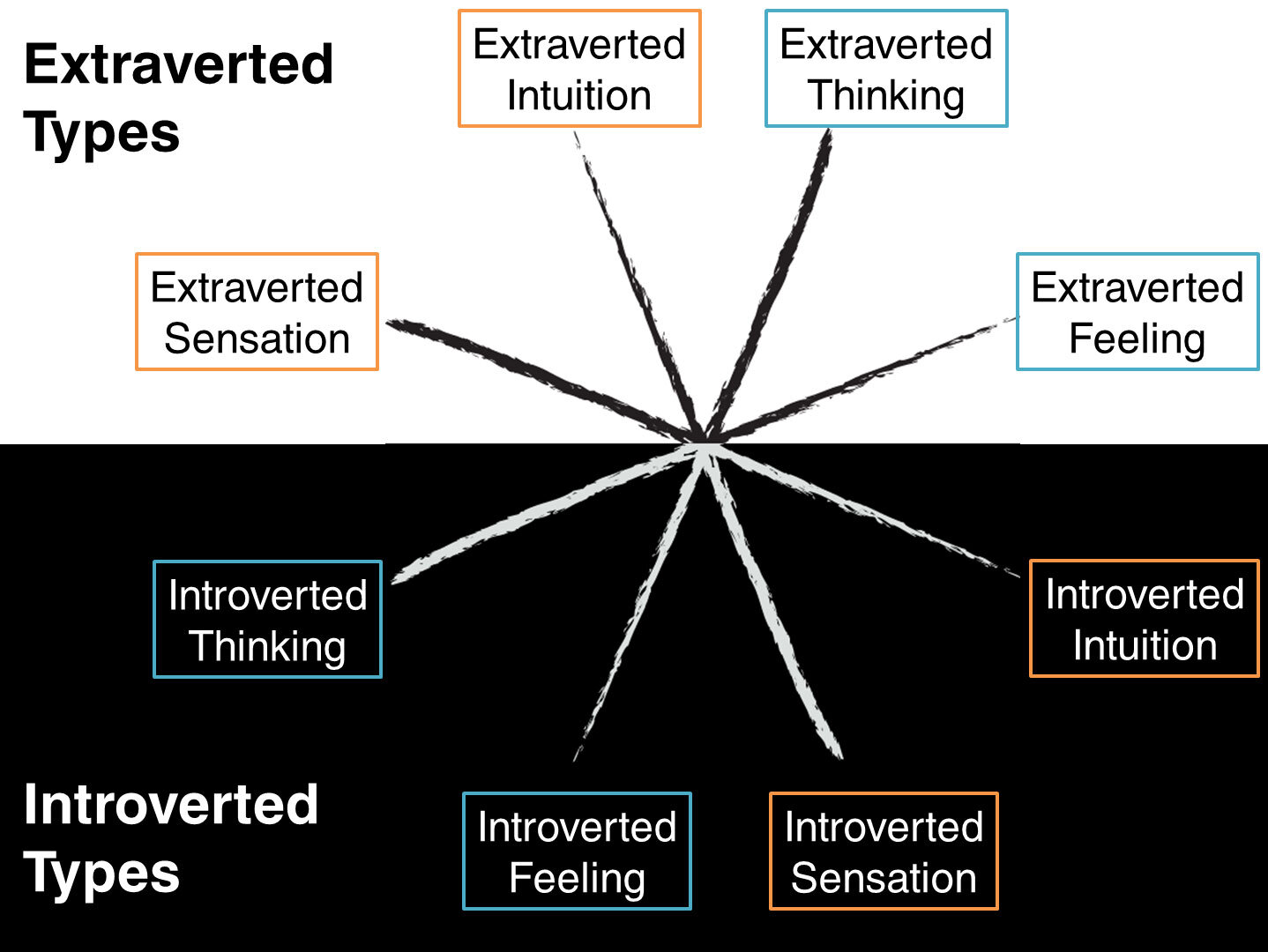

The four functions thus give us four basic function types: people for whom thinking, feeling, sensation, or intuition is dominant. This schema deepens, however, when we examine the intersection between attitude types and function types. Jung noted that “no individual is simply introverted or extraverted…[but] is so in one of [their] functions” (p. 519). In other words, each of our psychological functions can be oriented primarily outward toward external objects or inward toward their archetypal roots. Thus, we can think about eight primary types determined by the superior function of the personality:

Illustration of Jung’s eight function-types.

In Psychological Types, Jung elaborates on each of these eight types in significant detail, and I hope to describe them in future posts. The eight function-types each operate quite differently and with rich arrays of strengths and weaknesses that are worth exploring and pondering.

The Total Personality

We are now in a position to sketch the operation of the total personality. Jung’s model of the psyche makes much of opposing tensions and compensations. He observed that the strength of operation of one rational or irrational function corresponds to a weakness in its paired function. Just as when I am looking forward I cannot see what is behind my head, so too when I am relying on analytic thinking I cannot simultaneously attend to the worth and value of the conclusions I am trying to reach, lest it interfere with and muddle my reasoning. Regarding sensation and intuition, Jung writes, “When I try to assure myself with my eyes and ears of what is actually happening, I cannot at the same time give way to dreams and fantasies about what lies around the corner” (p. 539).

Putting Jung’s principles together, it is easy to see that the superior function implies a corresponding, counterbalancing inferior function that is least under conscious control. Marie Louise von Franz (1975) referred to the inferior function as “the ever bleeding wound of the conscious personality” as well as “the door through which all the figures of the unconscious come into consciousness.” Much could be said of the inferior function, but in brief, it is readily identifiable via our persistent foibles, troubles, and embarrassments—the part of ourselves that seems to “just happen” to us despite our best intentions and resolve. The inferior function tends to pop out when we are stressed, anxious, or intoxicated, and frequently comes to be associated with our shames and failures.

You can immediately determine the inferior function from the superior function (or vice versa), as illustrated in the diagram above. Simply flip the attitude and go to the opposite function in the function pair: if the superior function is extraverted, the inferior function is introverted, and vice versa. If the superior function is a rational function, the inferior function is its complementary rational function: thus, thinking types have inferior feeling functions, intuitive types have inferior sensing functions, and so on. One can never have superior and inferior functions that are both extraverted or both introverted, since a conscious orientation always implies an unconscious compensation and vice versa.

Finally, Jung observed the superior function has a sidekick function: “for all the types met with in practice, the rule holds good that besides the conscious, primary function there is a relatively unconscious, auxiliary function which is in every respect different from the nature of the primary function” (p. 406). What Jung means here is that the auxiliary function has the opposite attitude as the superior function (so if the superior function is extraverted, the auxiliary is introverted and vice versa), and that the auxiliary function will be an irrational function if the superior function is a rational function, or a rational function if the superior function is an irrational function. Thus, if your superior function is introverted intuition, your auxiliary function must be either extraverted thinking or extraverted feeling.

The final function, the tertiary function, is to the auxiliary function as the inferior function is to the superior function, though with less intensity. Thus, the tertiary function operates largely unconsciously, though not with the same pull toward negativity and failure as the inferior function. Of the auxiliary and tertiary functions, one is introverted and the other extraverted, in the same counterbalancing orientation as the superior and inferior functions.

Summary

To briefly encapsulate what we’ve covered thus far, Jung’s model of the personality is built up of a handful of basic component concepts and principles:

-

The 2 attitudes of extraversion and introversion that show how one directs energy toward external objects or internal archetypes;

-

The 4 necessary, sufficient functions (sensation, intuition, thinking, and feeling) for orienting to the world;

-

The primacy of the unconscious operation of the psyche, and the principle that development proceeds in the direction of making the unconscious conscious;

-

The principle of conscious-unconscious complementary and counterbalancing, such that every conscious/extraverted orientation implies an unconscious/introverted operation (and vice versa).

Putting this all together, we can see that Jung’s model implies 16 types: 4 functions, one of which is superior and can have 1 of 2 attitudes (extraverted or introverted) makes for 8 basic personality types, which are then multiplied by 2, since once we know the superior-inferior function pair there are only 2 possibilities for what the auxiliary function can be. Once the auxiliary function is known, the tertiary function is entirely determined.

If you approach the 16 types from the perspective that each of them represents not just one idea, but a complex arrangement of balanced strengths and weaknesses, Jung’s model can provide a helpful framework for empathizing with and understanding ways of being in the world that are quite different from your own.

References

Jung, C. G. (1921/1971). Psychological Types. Princeton/Bollingen.

Kant, I. (1781/2011). Critique of Pure Reason (tr. N.K. Smith). Read Books Ltd.

Nietzsche, F. W. (1966). Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future. (W. A. Kaufmann, Trans.). Modern Library.

von Franz, M. L. (1971). The inferior function. In von Franz, M. K. & Hillman, J. (Eds.), Lectures on Jung’s typology, 73-150.

Pingback: Jung’s Notions of Extraversion and Introversion - Depth Psychotherapy in the Berkshires: Rain Mason Olbert, PhD

Comments are closed.